Hacking Digital Democracy... and the History of Computerized Elections. (Part I)

1. Introduction

What makes electronic voting so unique?

The core truism of any competitive environment, from sports to business, is that any iron laws or codes of conduct and ethics can and will be breached at some time, at some place, by a competitor who deems it beneficial or, in a bout of despondency, necessary, to resort to such isolation and elimination of competition; this behavior can be expected to continue until the administrators of that competitive environment ascertain the nature of the cheat and mete forth proportionate and nullifying punishment, or establish structural blockades attenuating any net benefits extracted by anti-competitive behavior, whilst accelerating the cost of engagement.

The natural evolution of this truism brings attention to how it might unfold, and be quantified, with respect to electoral politics, wherein the benefits those who would so betray the public trust stand to reap is immense. The tactical repertoire that they might draw from is well-documented, from disinformation campaigns, subversive robocalls, flyers telling people to vote after the election, implementation of restrictive laws suppressing the vote, caging, gerrymandering, voter coercion, intimidation and bribery1 — some implementations become egregiously obvious if not for the general lack of legal infrastructure to combat such fraud.2 But that is besides the point of this article; the focal point of discussion regards how these actors might exploit the process of vote-counting itself, the, at present, heavily-computerized substrate of the democracy that confers into them their fortunes, and their tragedies. At the center of that discussion is what are the tools they have at their disposal to accomplish these ends?

For the greater part of the 20th century the most common way to cast and count votes was through the use of bulky, half-ton mechanical behemoths known as lever voting machines.

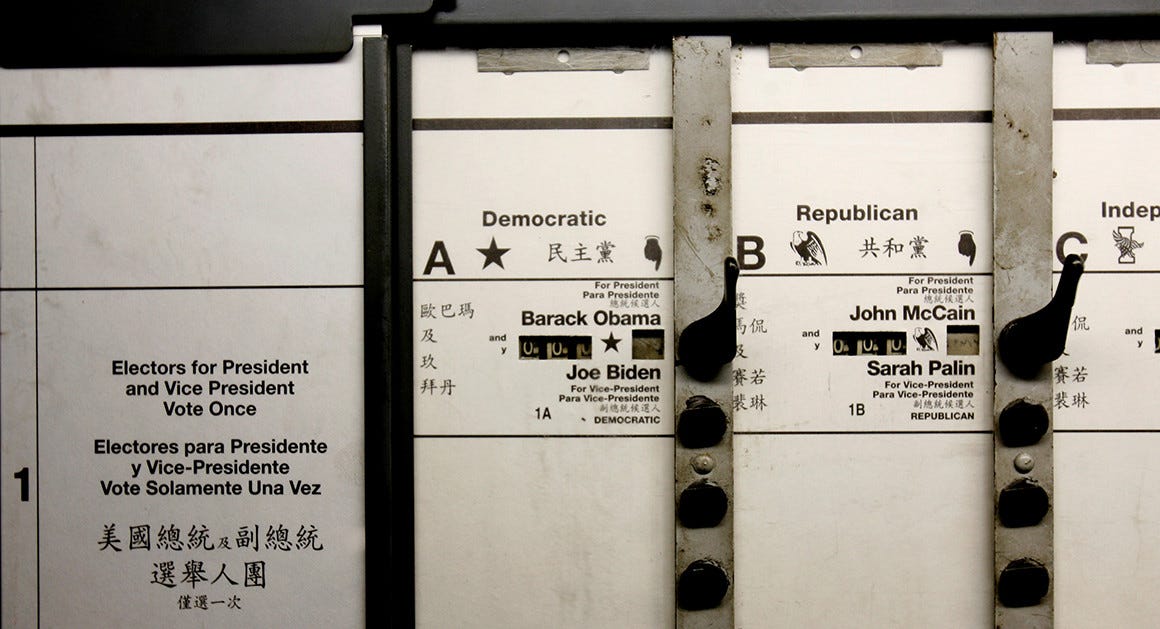

As the technological pinnacle of American democracy, for whose perennial status quo they dominated and represented, the common perception was that the era of lever voting would last forever. By 1964, two-thirds of the country lived in jurisdictions where votes were cast and counted by lever voting machines — the remaining third lived in areas where paper ballots were tabulated transparently and observably by hand. But, as it turned out, this era was temporary and would come to pass. By 1982 the stagnant duopoly of manufacturers responsible for developing and servicing these machines, the Automatic Voting Machine Corporation and Shoup Voting Machine Corporation, would cease their production and make forays into other technologies or get absorbed in the late-20th century concentration of the election market, but the voting machines themselves would remain staples of the democratic process until the early 2000s.3

The basic lever voting setup consists of a voting booth that secures voter privacy, equipped with a terminal with a display “ballot” laid out on its front. Candidates and parties would be listed in a tabular format, with candidate names on the row axis and party affiliations on the columnar axis, and a lever placed at the intersection of these axes. Voters would pull these levers and the counters installed on the backside of the front panel, which are not dissimilar to the odometer of a car, would record the cumulative tally of all votes cast for that candidate. Levers would have locking mechanisms that would prevent double voting or overvoting. Since the machines do not create records of each individual voter choice, recounts are impossible in the case of error or fraud,4 and the machines were difficult and expensive to test so jurisdictions generally enlisted the help of outsider technicians to perform those duties for them, meaning that, if somebody wished to buy an election all they would have to do is buy up support in those responsible for maintaining the equipment.5

The tactic du jour would be to send a technician to fix the vote counters, whose totals could not be independently adjudicated for a lack of voter-verifiable paper records or ballots, to display a given vote total. This could be done before Election Day in order to establish a vote 'floor' which is known to the attacker before a single vote has been cast and can plan accordingly. The attack might instead involve reducing the vote count for one candidate or issue by -x votes and increasing the votes for another option for the same contest by +x votes, keeping the vote totals the same and, in places where proper accounting measures are used to deter ballot box fraud, it would pass that measure and the election would be certified. Of course, that assumes that cooking the pollbooks isn't within the purview of the attackers.

This has the critical limitation that it, even in ideal conditions of absent oversight from county administration, requires the dispatch of a team of corrupt technicians to tamper with every individual machine, in every precinct in a county, and, if desired, across multiple counties or the whole state. The logistics of such an operation makes fixing statewide elections or even a presidential election next to impossible, and doing it secretly is unthinkable. Perhaps, if county elections are administered by insiders affiliated with that political machine or political party, then it would make sense, but, beyond county-level politics rigging lever voting machines makes little sense, except for cases where the outcome of a extraordinarily close statewide election can be manipulated by vote count rigging in a single, high-population county.

And then again, nothing about the setup of lever machines is electronic or digitized in any way; as the counters could not be infected with any type of brick-and-mortar ‘virus’, as anachronistic as that would be, set to tip the scales in favor of specific candidates or political issues, this cycling of technicians would have to be repeated before or after every election. That lever voting machines were manufactured by two duopolistic companies doesn’t really matter in this regard because elections are prepared at the county level, and as such, the absence of computerized components means that an insider at the assembly line cannot do anything to fix elections with said ‘virus’.

The other voting system was punch card voting.

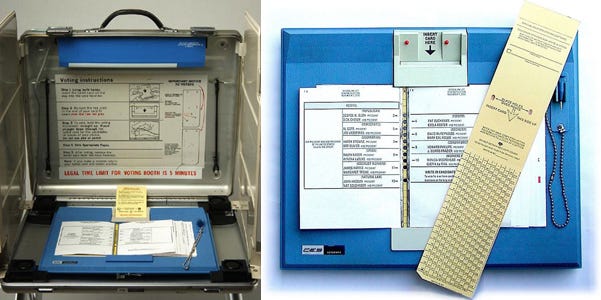

Voters mark their choices on a paper “ballot” by punching out a rectangle of perforated chad next to one candidate for every contested office on the ballot through use of a tool as simple as a stylus or, most often, through the use of a ballot marking device, or punched card voting machine. The resultant hole is then counted as a vote by a electromechanical punched card tabulation machine, a standard card reader or, in some cases, a programmable digital computer, which became more common near the century’s close.

Stemming from an origin in textile manufacturing that was eventually spun off for uses in data processing and U.S. Census data collection and tabulation, the first practical example of a voting system that utilizes punched cards to record votes emerged with the Votomatic, developed from the IBM Port-A-Punch card punching device for voting by Joseph P. Harris and William Rouverol. The Votomatic was later acquired by IBM in 1965, before selling it off. Later Votomatic machines (including the one pictured) were made by Computer Election Services Inc. and several other IBM licencees. CESI was later absorbed into Election Systems & Software.

The Votomatic was a mechanical ballot marking device that translated voter intent into a vote on a physical, pre-scored punched card, containing a dense layout of voting positions accommodating complex ballots. The punch cards are not verifiable by voters for a lack of candidate nominal signage next to each hole, so it is impossible for a voter to know, unless if they have access to ballot design files for that jurisdictions, if their votes were punched properly. The other popular configuration is the Datavote card punching machine, which is combined with punch cards that do have such signage, though at greater cost to the jurisdiction.6

As they are cheaper, easier-to-maintain and less cumbersome than their counterparts, these technologies quickly overtook the archetypical lever voting machine in popularity and widespread usage by the 1980s, and dominated the scene of American voting until their failure in the 2000 presidential election lead to their retirement. They had the perks of leaving behind a voter-created audit trail, not unlike a paper ballot, that could be examined in the event of a recount of an audit, though the error rates of card punching machines was generally high enough that a detected discrepancy in a single precinct due to fraud or improperly punched chads would be nearly indistinguishable.7

As non-programmable mechanical devices any perpetrated frauds would, again, have to be done by technicians with physical access to the machines, except for the locations that tabulated them digitally. “Hacking” a punch card machine is technically more difficult than modifying the numbers on a lever voting machine.

A strategy would be to have certain choices pre-punched in order to create anomalous overvotes that would be spoiled during tabulation, or to misalign the cards so that a voter who punches votes for one candidate would accidentally punch a vote for the other. Misaligned punch cards can create improperly punched chads that are still attached to the cards at the seams, generating false undervotes. At its broadest scale, the only effective fraud that could be mustered was by delivering punch card machines that couldn't count votes to strongholds of the other party.

The votes that get reported can be manipulated at the punched card tabulator, as well.

The original Hollerith tabulating machine was a device used to process masses of punched cards for the U.S. Census in 1890 with spring-loaded metal pins embedded into the card reader that were pushed down upon the inserted cards, and if a hole was punched for a given option then the wire for that position could be suspended into liquid mercury, completing an electrical circuit which powers a electromagnet mechanism that increments counters that record the number of instances that particular position had been invoked as best describing the citizens theretofore included in the Census count.8

Under the assumption that the electromechanical punched card tabulator used after the fifties aren’t conceptually dissimilar from the Hollerith tabulating machine then it's conceivable that an engineer would map the counter recording punched votes for one candidate to another candidate and vice versa, effectively reversing the result for that machine. The same process must then be repeated for every such machine being shipped to the pertinent jurisdiction, implying that the engineer has the graces of the manufacturer.

This comes at great cost to the manufacturer and is not exactly flexible. A “fire and forget” dynamic, the rig would not be particularly useful in a volatile election environment. If a sudden pre-Election Day surge in support for the fixer’s favored candidate who was projected as the underdog by their pollsters results in them winning in the court of public opinion, then not only is the rig superfluous but also self-destructive, and there is nothing the fixer can do about that. The company will have no control over the vote flipping in future elections, and who benefits from the rigging.

The transition from the precinct-count configuration to the central processing of voted “ballots” still made vote rigging far easier to do manually, since the vote data recorded by the tabulator's counters can be manually manipulated after the election like a lever voting machine, but counties would only have one punched card tabulator as opposed to dozens of hundreds of lever voting machines for each polling place.

Nonetheless, both of these voting types are still quite decentralized and hard to penetrate on a scale that extends beyond the utility of local political bosses. The fraud of old could only clearly serve the purpose of swaying the tide of close elections9 or ones far enough down the ballot that the predicted electorate would exceed no more than a few thousand votes, padding the vote in partisan fiefdoms, or perhaps as indemnification or a display of loyalty to political patronage. Electoral fraud was a egalitarian free-for-all and produced a net wash because vote rigging would not strictly favor any party over the other and could not effectively be executed at a national scale, with the exception of good-old fashioned voter suppression.

It is from the development and speciation of these technologies that electronic voting emerges. Direct record electronic voting machines are quite straightforward, consisting of a touchscreen interface which voters use to electronically submit votes, which they will cast after reviewing their selections on the screen.

Optical mark-sense scanning, or optical scanning, was developed as an alternative to IBM's electrical system. IBM had explored optical mark sensing in years earlier, but Professor E. F. Lindquist of the University of Iowa developed the ACT exam and directed the development of the first practical optical mark-sense test scoring machines in the mid 1950s. The rights to this technology were sold to the Westinghouse Learning Corporation in 1968, and Robert J. Urosevich of the Klopp Printing Company presided over the trialling of this tech for the scanning of voter-marked ballots in 1974. Urosevich’s company, Data Mark Systems, would ultimately license the tech after it was abandoned by Westinghouse.

The very first mark-sense scanners used for grading papers detected graphite pencil marks or insulating ink made on conductive stationery by sensing the slight difference in electric conductivity of the two media. Mark-sense ballot scanners, such as the Votronic Corporation ballot scanner that dominated during the late sixties and early seventies, to modern optical scanners, use light-emitting diodes and photosensors to scan votes filled in by voters using non-reflective ink.10

The ballot would be illuminated by the diode, whose light would be absorbed by the ink, and the ‘gap’ would be interpreted as a vote by the scanner. The vote data would be logged into an electronic storage medium such as a memory card. Optical scanners can be used in a central-count, batch-fed configuration, similar to the punch card tabulators, which is often used to process large quantities of absentee ballots though some areas use it to aggregate in-person ballots, too, or precinct-count configuration, used chiefly to count in-person ballots cast on Election Day or during early voting.

The processing of ballots and punched cards for these two devices is coordinated centrally by a programmable memory card or control card. The code on these removable electronic storage media, the former of which are small enough to fit on the tip of your finger, store vote-counting logic, records of votes cast and counted by the machines, audit logs, and so forth. With mechanical voting systems and punched cards counted by electromechanical tabulators, changing thousands of votes takes much material effort to execute. Changing numbers on a memory card takes seconds. Additionally, they can be programmed with malicious counting logic that reacts semi-intelligently to variables supplied over the course of an election. If the desired candidate is winning the real count, then nothing is done, and if they are trailing, the code can add votes to their running total, whilst subtracting votes from their adversar(ies)y’s totals, until the desired candidate eclipses them and achieves a commanding plurality.

Provided that the yet-still gestating Internet would not escape its infancy until the late eighties, these computers would not be networked and thus vulnerable to very much outsider interference. Rather, the worry was that a corporate insider, with unfettered access to the manufacture and programming of these devices, can install undetectable malware into the memory of the computers that manipulates vote data stored invisibly as abstracted numbers on a memory card, unseen by a human being, and unilaterally perpetrate fraud at an unprecedented scale without much risk of being detected. All they would need is a political or financial interest to motivate them to commit these crimes, and the will to stomach it.

The principal practical vulnerability of the digital age is invisibility. The internal processes and events of computer programs are not liable to be subject to any kind of oversight or observation by all but a few highly-educated and technical-savvy users. Checking the windows and locking the doors is not possible — yet still, it remains implausible to design a perfectly secure computer, and they are still exceptionally vulnerable to fraud and theft.

Thus, it is with these digital, programmable, computerized voting systems that the fears that they could be used to propagate election fraud at a unprecedented scale and irrecoverable error began to take shape. First, it was the digital punched card tabulators that jurisdictions began to adopt during the seventies and eighties that received much of the attention.1112

The company at the center of everyone’s attention was also the largest; Computer Election Systems, Incorporated of Berkeley, California. Contracting out to over 1,000 county- and municipal-level jurisdictional governments by the mid-eighties, it was accused by many politicians running for elected office of facilitating vote fraud across the states of Indiana and West Virginia, which, naturally, its president, John H. Kemp denied, though while conceding that designing a fraud-proof system is infeasible or even impossible.13

In West Virginia, three-term Charleston mayor John Hutchinson charged that several Kanawha County election officials and Computer Election representatives successfully conspired to deprive him of his re-election in November 1980, citing pre-election polls that showed him winning overwhelming there despite the recorded loss.14

In Dallas, Terry Elkins, the campaign manager for Max Goldblatt, who in 1985 ran for mayor, came to believe, on the basis of a months-long study of the surviving records and materials of the election, that Goldblatt had been kept out of a runoff by manipulation of the computerized voting system. Impressed by the charges, the attorney general of Texas, Jim Mattox, conducted an official investigation of them.15

Whether these allegations of fraud could be proven, and if they were based in reality and not cynical politics, is besides the core point; the specific allegation that was corroborated by the testimony of multiple experts and computer scientists was that these systems were insecure and ripe for fraud. Howard Jay Strauss, the associate director of the Princeton University Computer Center, who formerly worked at Bell Laboratories, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and the RCA Corporation, had confirmed that the program used to count Indiana votes was vulnerable to manipulation. An attacker could punch bogus votes into the punched cards, or control how they are counted by the tabulators, whilst purging audit log evidence of their intrusion.16

The New York Times also sought the counsel of Eric K. Clemons, an associate professor of decision sciences at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, who backed up those claims.17

For a technology so new, few states had adopted coherent standards and guidelines that the computerized election systems would be accordingly tested and certified against in order to ensure their security, reliability and accountability. The state of California’s chief voting system certification consultant, Robert J. Naegele, who had been hired by the Federal Election Commission in 1987 to draft the basis of the voluntary federal recommendations and standards for the certification and adoption of electronic voting machines and tabulators, portions of which stand to this day,18 stated in ‘88 that “when we first started looking at this issue, back in the middle seventies, we found there were a lot of these systems that were vulnerable to fraud and out-and-out error.”19

And as such, the course of electoral democracy becomes their’s to lose. A single programmer, or a small group of motivated, technically-skilled conspirators, now has the ability to perpetrate fraud at a massive, unprecedented scale, with any impedance originating from the sole limiting factor of the market dominance of the company that the programmer works for or whose vulnerabilities they are exploiting. When monopolies in the election market begin to coalesce, the business of election rigging itself becomes a monopoly, the sole domain of whomever the company has set its sights upon.

The election market of the eighties was, however, not yet centralized and monopolized. Without that, such insider fraud would be restricted to a smaller scale — not as localized as the fraud of old, but not quite enough to tip the scales at a national level, except for in the narrowest elections, determined by a handful of state and fractions of the total vote.

The earliest systems were built by an ecosystem of numerous small and relatively localized mom-and-pop election vendors operating in a healthy, competitive market, that generally persisted in their own parochial niches and supplied counties with supplies and vote counting equipment. The very first direct recording electronic system to be sold for real world election use was the touchscreen Video Voter, developed McKay, Ziebold, Kirby and Hetzel in 1974 (U.S. Patent 3,793,505)20 and marketed by the Frank Thornber Company, which was deployed for use in 1975 in Woodstock and Streamwood, Illinois, before other counties in the state bought and used them over the course of the following years. Then there was Western Data Services Inc., a firm that provided on-line computer services to several hundred county and municipal governments, school districts and other governmental agencies in Texas.

This framework would be dissolved in a frenzy of acquisitions and mergers by the nineties, wherein the great majority of them had been subsumed into the corporation that would eventually be incorporated into what would become known as ES&S. During the mid-eighties and nineties, the Business Records Corporation of Dallas, Texas, the sole and wholly-owned subsidiary of Cronus Industries, embarked on an expedition to corner the market.21

In July, 1984, BRC began its expansion with the acquisition of Data Management Associates of Colorado Springs and the C. Edwin Hultman Company, before moving to absorb Western Data Services Incorporated of Texas, Roberts & Son Inc. of Birmingham, Alabama, and Frank Thornber Co. of Illinois. By the end of 1985, Cronus Industries had finalized its purchase of Computer Election Systems, Inc., and in the months following BRC had further acquired Integrated Micro Systems Inc. of Rockford, Illinois, and merged with Computer Concepts & Services, Inc. of St. Cloud, Minnesota in 1986, and subsumed Sun Belt Press Inc. of Alabama and Minneapolis-based Miller/Davis Company.

The result of the acquisition blitz was to eliminate most competition, with the exception of a few large companies, and to operate virtual vote-counting monopolies in numerous states. They sold election services to the nation’s largest cities, in Los Angeles, Chicago, Detroit, Houston, Phoenix, Miami, Seattle, Minneapolis, Cincinnati, and Cleveland by 1988.22

Eventually, Cronus Industries would pivot its focus to healthcare consulting, and in 1997, American Information Systems, based in Nebraska, would come to seek the acquisition of BRC’s assets, after which it was reincorporated as ES&S.23 The Securities and Exchange Commission objected on antitrust grounds, and a deal was made in which the assets of BRC were shared between ES&S and another voting company, the burgeoning, California-based Sequoia Voting Systems.24 It is these two, together with two other corporations, Diebold Election Systems and Hart InterCivic, that embodied the election market at the dawn of the new century.

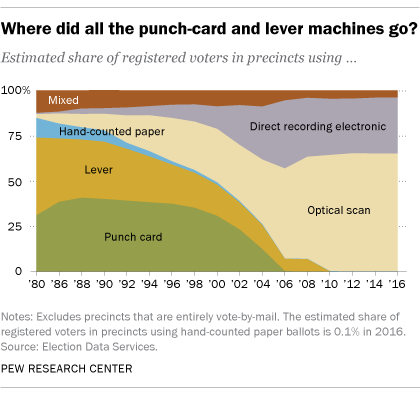

The transition to optical scanning systems and DREs began in the early nineties as the technology came to maturity and the promise for faster accounting and reporting of large amounts of votes was actualized, although they did not truly become common until the end of the century. After the voting debacle of the November 2000 presidential election in Florida, caused by thousands of lost votes due to card punching machines and unaligned ballot cards engendering hosts of ballots where voter intent could not be discerned by man or machine, election administrators and officials were neither ready nor willing to bear the brunt of the chaos — asymmetric recounts, vicious litigation, protests and riots — should such a scenario reach their jurisdiction, so they turned to the various electronic voting vendors for replace their aging equipment with newer, modern vote-counting computers, who proceeded to ruthlessly exploit the panic to force through their sales.

The old mechanical and punch card voting systems quickly collapsed in utilization as purely digitized voting became the mainstay of the 21st century. Direct recording electronic devices, once an obscure technology with limited market penetration which gradually grew through the nineties, swelled from less than 15% by 2000 to nearly 40% by 2006. Optical scanners, which had been displacing card punching machines and lever voting machines for a decade at that point, grew from 30% market share to over 40% in the same timeframe.25

The transition to all-electronic voting was supercharged, however, by the passage of the Help America Vote Act,26 which was signed into law on October 26th, 2002. Drafted in response to those voting failures and the resultant crisis of confidence in the administration of democracy, most important of its provisions was the order to phase out mechanical voting systems, and the disbursement of federal funds to jurisdictions across the country to replace these systems with advanced electronic voting machines or optical scanning systems, which were promised to make voting easier, faster, more reliable, and preclude the administrative debacles of the past. Beforehand, electronic voting systems were used by no more than 40% of registered voters in the country — including punch card counties, 55%. Afterwards, that quickly expanded to >99% by the top of the decade.

Lost, though, in the stampede to modernize, were the repeated demonstrations of insecurity and unsecurability. Over the course of the 21st century, from the beginning onto 2023, studies commissioned or contracted to computer scientists at the University of Princeton,272829 the University of California,30313233 the University of Pennsylvania,34 the Florida State University,35 Johns Hopkins and Rice Universities,36 the University of Connecticut,37 the U.S. Department of Energy's Argonne National Laboratory,38 cybersecurity contractors such as Virginia's Science Applications International Corporation39 and Michigan’s Compuware Corporation,40 and others4142434445 have served to expound upon the flaws and inherent absence of insurance pertaining to the security and privacy of vote casting and tabulation through these digital means, both in a laboratory and practical setting. They expose, both for systems in the United States and abroad, a distinct vulnerability to illegal and/or unauthorized interference, which, in any case, can be propagated by a single individual with physical access to a single machine in a given jurisdiction.

There was a difference between the election computer fraud of the eighties and that of the 2000s — these computers are heavily networked, paving the way for outsider threats as much as insider threats.

Network-based attacks can be mounted by outsiders by exploiting a crucial process in the preparation of elections: unlike lever voting machines precinct-count electronic voting systems and optical scanners have to be programmed centrally by copying election definitions into the memory of the machines, which are read by memory cards to facilitate the display of electronic ballots onto the glass screens of direct recording electronic machines, and to direct the process of discern deliberative intent from voter markings on ballot sheets. These election definitions are prepared by poll workers or election subcontractors at election management systems (EMS) in the central county election office, which most-often manifest as general-purpose workstations running commercial operating systems such as Windows or Linux. The definitions are generated and then copied onto removable electronic media, and dispatched to every voting machine in the county before they are sent to their designated precincts before voting begins. Alternatively, they are copied to voting machines via a LAN.

Ballot definition files can be modified to deliver a malware payload to the precinct voting equipment, or malware can be directly copied onto the electronic storage device and onto the voting machine, effectively jumping over the air-gap. Conversely, because of the programming process, infecting a single voting machine with malware provides the opportunity for it to infect the EMS via memory card, and subsequently all other precinct-level devices in the county — a single individual with temporary access to a single voting machine can compromise the entire election system of counties ranging from Loving County, Texas to all 22,000 such machines in Los Angeles County, California. The election management systems themselves are sometimes connected directly to the Internet; provided the equivocations of county election officials the extent to which is unclear, though such connectivity arrangements have been observed for months or years on end, without, allegedly, the knowledge of those officials. This provides a pathway for outsiders to remotely infiltrate county-level election networks and compromise voting software and election results, as well as future machine-aided recounts and audits, by modifying the election definition files to harbor malicious executables, which are transferred to voting machines.464748

The “secret”, that officials within all echelons of government, and vendors, often hate to admit,49 is that precinct voting machines are capable of connecting to the Internet, through modems or WIFI-capable memory cards, and have been for decades, sometimes without their knowledge. Cellular modems that can communicate with central election offices,50 have been used in voting machines and precinct optical scan tabulators to transmit (usually) unofficial results to the central EMS for aggregation and reporting for decades. It was, and probably still is (though it most likely wouldn’t make an inkling of a difference if it was not) the case that ES&S DS200 optical scanners equipped with networking cellular modems were in use across eleven states, numbering in the tens of thousands by some, admittedly napkin estimates. Hart InterCivic, similarly, admitted to selling 1,300 such Internet-capable tabulators in eleven counties in Michigan.5152

Because computers cannot be secured, it is up to election officials to implement comprehensive defenses against potential election tampering in all its forms. This includes devising certification standards and efficacious testing protocols to prevent insider-fraud, and effective post-election auditing or recount procedures in order to deter fraud which the chance that a hacker could be caught, thereby escalating the cost of hacking an election whilst decreasing the maximum gain one can extract by doing so.

The point of this article, then, is to examine the procedures in place and appraise their real value for achieving these ends, or to deconstruct them.

2. A “Brief” Description of the Election Market

“There is no reason to trust insiders in the election industry any more than in other industries, such as gambling, where sophisticated insider fraud has occurred despite extraordinary measures to prevent it.” — Report of the Carter-Baker Commission on Federal Election Reform (2005)53

A degree of certainty is enforced, in part, by the notion that, because our elections are administered over equipment supplied by a “broad” array of vendors, they evoke a sense of “decentralization” such that compromising every election system would be technically complex and orchestrating a manufacturer-side subversion scheme impossible.54 Perhaps in the eighties, this would’ve been true.

Of course, this is not the eighties. Technically the mores of election administration are decentralized in the sense that there are a lot of counties subdivided into a lot of townships, each with their own election officials, administrators, judges et al. This, critically, only serves to make election adjudication even more difficult in the case of a successful attack or other procedural error and only represents a roadblock for hackers, particularly of the state-backed kind. It is, rather, a boon for corporate insiders,55 however, since ballot design and voting machine programming is highly specific to a given jurisdiction due to local races like for mayorship, school board, water retention services and so forth. This means that the programmer will necessarily know the location that every memory card and every ballot definition file will be sent to will extreme precision, allowing for demographic-based attacks if they are desirable or necessary.

By contrast, the elections market, crucially, is not decentralized. At present, the market of vendors is highly centralized and concentrated into a tight oligopoly of three companies, each with various political agendas and tribulations unto themselves: the Omaha, Nebraska-based, Election Systems & Software, the Toronto, Ontario-based Dominion Voting Systems, and Austin, Texas-based Hart Intercivic. Combined, their voting equipment services north of 88% of registered voters across the country, with the remainder being handled by a smaller carnival of vendors with a none-too-much better track record, as we will see shortly, at least in the respect that anyone has done any research on them.56

The politics of bidding for jurisdictional contracts is a complex process but more often then not transpires in a way not dissimilar to a racket; a common observation in the world of election administration is that election officials, well-intentioned as the median individual might very well be, are, lacking in the requisite technical expertise, largely in the dark about the inner workings of the various black box voting systems and usually resign to the explanatory caprices and hail of fact-averse marketing pitch proudly spread by amoral election vendors unconcerned with actual (i.e. not because nothing better exists) customer satisfaction. Such naivety ends up getting exploited in the world of election market hegemonies and corporate gangsterism, where honesty is a deadweight, the lengths of which these contractors will consider necessary to maintain their gaping share of the market can be quite egregious: lobbying, extortion, deception and even outright bribery.

Voting machine vendors will utilize the tools disposed to them to command the unfailing allegiance of the officials charged with the drafting of legislation and election management functions on the county or state level, first with undermining the very structure of U.S. elections and establishing an inescapable codependency between themselves and the administrators that have made the grave error of contracting out to them.

The prime example of this dynamic was provided in Angelina County, Texas, just before the 200857 presidential general election cycle; the county depended on ES&S to provide and deploy election equipment and supplies, design paper ballots, pre-marking ballots for pre-election testing, the programming of iVotronic voting machines, service the voting machines designated as accessible for disabled voters with audio functions, burning memory cards, electronic vote cartridges and flash drives for the M100 ballot scanners and iVotronics, set-up the Election Night vote reporting manager program, and administer Election Day support, retrieve results and report outcomes. This all gave the contractor considerable sway to extort the county administrators into signing agreements to clean up ES&S’s own election reporting mess, by recounting ballots using the very reporting manager program serviced, at an expensive price, by ES&S. If the county did not then the company could simply withhold support and let future elections collapse. Testimony and documents from many other counties across the country demonstrated that this dynamic was fairly common.58

Among HAVA’s mandates is the requirement for at least one ADA-accessible voting device per precinct or polling place, but New York, which was still using its antiquated (and quite effective and hard to hack) mechanical, lever voting machines, missed the federally-mandated deadline. As a result, by January 2008 U.S. District Judge Gary L. Sharpe granted a motion to enforce and ordered counties to deploy at least one ballot marking devices for disabled voters by the September primaries. With only eight months to comply with the court order, Nassau County, along dozens of other counties, contracted out to Sequoia Voting Systems59 for hundreds of its ImageCast optical scanner/BMD hybrid voting machines, effectively indenturing itself to its whims. By June 26th, the county had received 156 of its ordered machines, yet 85% of them were rendered unusable by printer failures, USB problems, battery drain, no responsive keypads, physical damage, and so forth. Similar failures were reported by other counties across the state, yet Sequoia took its sweet time fixing them, and, months afterwards their diagnostic functions were still out of order.60

Hawaii was another example of a state whose elections were virtually entirely privatized by corporate vendors. In the early 2000s ES&S and Hart InterCivic handled everything, from election programming, ballot design and all technical work. Volunteers administered elections on the precinct-level, but after the polls were shuttered on Election Night and the memory cards were removed from precinct voting machines they were handed off to corporate technicians and the vendors handled tabulation and vote reporting. This led to problems such as machines reading votes for Green Party candidates despite the fact that they ran no candidates for the affected races, or election officials having to revise turnout estimates because the vendors calculated them differently from one another.61

By 2008, Hawaii had awarded a contract to Hart InterCivic that gave them a complete monopoly over the state’s elections, which ES&S challenged on the basis that Hart's bid was unreasonably pricy, automatically triggering a stay on the contract.62 Eventually, the contract went through when Craig Uyehara, an administrative hearings officer for the state Department of Commerce and Consumer Affairs, ruled that, while the contract was awarded in bad faith, it was too late to renege it, lest the 2008 primary elections and onward be thrown into jeopardy.63 The state was so dependent upon corporate support that it believed that upholding an invalid contract was necessary to run elections. Hart InterCivic still runs Hawaii's elections to this day.

Election programming is a process repeated, necessarily, for every election and is not subject to any sort of testing or oversight by federally-accredited or state-level agencies. However, since most counties, mainly rural, though some larger urban counties exempt this rule of thumb, lack the fiscal resources, and therefore qualified staff and technical experience to maintain the electronic voting equipment that run their elections, this process is often contracted out right back to the vendors themselves, or subcontractors.64 The concentration of this programming into the hands of the vendors has lead to dozens of reported cases of the results of elections being reversed and victory misattributed to the wrong candidate65 — and these are only cases detected by officials. If ballot programming errors mapped, for example, Democratic votes to Republican votes and Republican votes to Democratic votes for a single race then, perhaps, the mismatch of the results of that race compared to other partisan-contested races would make the programming errors obvious, but if the misattribution of votes applies to all candidates in all races, then it would not be so obvious. Nevertheless, hundreds of jurisdictions still continue to pay these vendors to program their ballots despite the many observed flaws, and outright incompetence.

A major component driving these dependencies is the fact that the laws of some states statutorily impel, either explicitly or implicitly, election officials to acquire equipment or fulfill requirements that can only be fulfilled and supplied by vendors, no matter how flawed their operations are. These provisions corner officials into purchasing from inveterate and often security/consumer satisfaction-agnostic corporations, rather than establishing independent voting systems with the guidance of seasoned cybersecurity experts. Many states require that counties purchase from companies that have their equipment certified by the two federally-accredited test authorities, which sounds good on paper, but, due to the extravagant contract pricings they charge for their compliance testing only well-established vendors can afford, which has the dual-effect of accelerating reliance on large vendor corporations, and introduces market barriers for smaller competition.66

Because of the legal setups forcing counties to bargain for often-failed and insecure voting systems from untrustworthy vendors, the general, unspoken rule of the election industry is that, once you bought it, you keep it. Sometimes this rule is summarized honestly by vendors. Internal emails authored by Ken Clark, Principle Engineer of Diebold Election Systems,67 and later leaked and made publicly available on the Internet, read that “there is an important point that seems to be missed by all these articles: they already bought the system. At this point they are just closing the barn door. Let’s just hope that as a company we are smart enough to charge out the yin if they try to change the rules now and legislate voter receipts.”.68

When asked to clarify the meaning of “out the yin”, Clark wrote further: “Short for ‘out the yin-yang’. ...Any after-sale changes should be prohibitively expensive. Much more expensive than, for example, a university research grant.”69

In accordance to this iron law, ES&S began gouging the costs of maintaining the (often-failed and unreliable) election systems it doled out to contracting counties. In Webster County, Iowa, the budget set aside for election operations expanded from $49,000 to $110,700 for only 25,300 registered voters across twenty-five precincts over the course of two years from 2005 to 2007. The vast majority of this cost came from extortionate ES&S maintenance fees for the county's new Model 100 ballot scanners and AutoMARK electronic voting machines.70

The standard-issue corporate greed was varnished with a dash of ambition, too, since the contractors working for Sequoia Voting Systems were allegedly ordered, despite any ethical qualms they may wish to bring to bear, to deliberately supply counties in Florida with substandard punch card ballot paper that didn’t punch properly, manufactured at a paper mill with zero experience printing punch card papers, ahead of the 2000 general election with the knowledge and sanction of the company’s management. The company even modified the specs of paper punch cards sold to Palm Beach County, leading to piles of undervotes and improperly punched chads, an action which very effectively spurred a crisis after the election that discredited punch card voting, and drove the country’s transition to all-electronic voting, a dynamic which is, evidently, quite good for business.7172

The programming of voting equipment is considered to be proprietary, subject to fiercely guarded property rights, a dynamic where the code is known only to the corporate programmer and no-one else, except for perhaps an “independent (in name only) testing authority” that inspects the code, and a lucky few independent researchers.

The excuse is that open-source programming would ultimately be harmful to the security of the system by revealing the inner-workings of the system to potentially malicious outsiders, a principle known as security in obscurity, despite the cybersecurity community’s virtual unanimity regarding the inefficacy of obscurity as a useful security solution73 because hackers can still acquire the source code through extralegal means, or insiders can perform drill-downs into the code, and now knowledge of vulnerability is privatized and unlikely to be patched on a timely, meaningful basis.

Of course, the idea that these vendors actually care about security has been found in the breach on many occasions.

An example is given in 2003 when a small team of researchers from Johns Hopkins and Rice University analyzed only the unencrypted portions of the source code repository for the Diebold AccuVote TS voting machine that was discovered on an unsecured company FTP Internet server by voting activist Beverly Harris earlier that year,74 and found that it was easy to generate fraudulent smart cards that could be used to allow voters to submit multiple votes, obtain administrator privileges and review partial results and shut down the election early, vote totals aren't encrypted when transmitted to the count election office, meaning that they can be intercepted in a man-in-the-middle attack if transmitted by phone line or over the Internet and manipulated, and whenever cryptography is used it's used incompetently. Diebold disregarded the findings of the study, claiming they are not reflective of the protocols of a real election. Afterwards, Maryland, whose board of elections had been considering finalizing the purchase of Diebold touchscreens, contracted out to the Science Applications International Corporation, whose report largely confirmed most of the findings of the Johns Hopkins/Rice study.75 Diebold spun both studies as confirming the integrity of its systems76 and that any and all problems stem from management issues (“human error”), which the state Board of Elections accepted.

Another study, also commissioned by Maryland, out to the company RABA Technologies,77 again confirmed the findings of the previous two studies, this time in a simulated election environment inspired by the state’s election administration, netting the AccuVote-TS a failing grade.78 Still, Diebold managed to spin this too.79

Security analysis conducted three years later revealed that most all of the vulnerabilities discovered before and during the Maryland certification process had not been addressed by Diebold at all; if anything they were more numerous than before.80

The deceit culminated in October, 2006, when a disk containing a certified copy of the Diebold BallotStation program and Global Election Management Software (GEMS) database source code used to tally votes was possibly stolen, which Diebold denied, and then apologetically claimed that, even if it were real (it was) it would take a “knowledgeable scientist years to break the encryption”. BallotStation source code was found not to be encrypted in the least.81

Diebold, at this point infamous for its negligence — among the cybersecurity and election integrity community, not election admins, who continued to contract out to the company until its insolvency, mostly because they were never alerted by the “information clearinghouse” Election Assistance Commission — enlisted its lying spokesman to besmirch the findings of the UC Berkeley Top-to-Bottom review commissioned by California Secretary of State Debra Bowen as having unrealistic access to company-provided source code, and that existent “checks and balances” prevented the hacks from occurring in real life.82 Not only did the Red Team Top-to-Bottom review83 explicitly not have access to the system's source code,84 but the “complete and unlimited access” assumed (fallaciously) to be required to hack a voting system is already available to Diebold insiders and poll workers. The ultimate example of this was that, in 2007, sitting out in the open, in the cold, unsupervised darkness of the company's warehouse in Allen, Texas, were stacks upon stacks of optical scanning systems which were easily hackable and accessible to all sorts of insiders and burglars, who could infect the devices with malware, undetected, and they'll still be shipped out to the counties as though nothing was amiss.85

In Ohio, a former high-level technician of Hart InterCivic by the name of William Singer filed a Qui Tam false marketing lawsuit on behalf of the federal government in 2007 alleging that the company deceived both the government and county customers about its eSlate voting machine in order to pony up a slice of the $3.9 billion HAVA appropriations pie and win contracts. Activities that the company variously engaged in in order to illicitly acquire those funds include routinely failing to properly test its voting equipment (botched alpha tests and zero beta tests to catch “major” and “minor” flaws respectively), deliberately avoiding the process of properly certifying its eSlate voting machines by the submission of unmarketed dummy voting machines that voting system test labs would “certify” for use in Ohio, then substitute it for the real, uncertified product upon delivery, hand fabricating election abstract reports that the eSlate system could not produce and submitting to the Ohio Secretary of State in order to acquire state certification, submission of false reports to InfoSentry during its state of Ohio commissioned examination of voting systems86 to give the false impression that Hart provisions for disaster plans and security audits, lying about the lack of voting system capacity to store vote data truly randomly (only pseudo-randomly) allowing insiders to breach ballot secrecy with reasonable certainty as to how voters voted, issuing software patches to some of its eSlate voting systems but not others whilst not alerting anyone about it after Singer discovered that the audit logging function for the Ballot Organization Software System used to create and design ballots produced invalid entries and was rendered useless, falsely marketing the M2B3 memory card reader as being faster and less prone to data corruption than previous card readers it sold, and so forth.878889

In the aftermath of a purported failure of their AVC touchscreen voting machines in the 2008 New Jersey primaries,90 Sequoia spent its sweet time drafting press releases ballyhooing its dedication to third-party reviews of its equipment whilst simultaneously threatening Princeton scientists with legal retribution if they took a crack at their “tamper-proof” easily hackable voting systems.91

Instead, its Vice-President of Compliance, Quality and Certification, Edwin B. Smith III, kicked the buck over to the completely unknown Kwaidan Consulting Services supposedly based in Houston, which had no website and was a one-man operation headed by a figure of questionable character who used to work at the company that became Suntron, which manufactured Hart’s troubled eSlates.9293 Perhaps there is no correlation between Suntron and Sequoia, but provided Ed Smith’s former employ at Hart InterCivic that hope is unlikely.

When maverick election officials take the responsibility of ensuring the integrity of the technology of democracy into their own hands they often find themselves at the receiving end of an assault by election vendors and their vanguards implying that there would be hell to pay for their transgressions. Such was the case of Ion Sancho, Supervisor of Elections in Leon County, Florida, who in 2005 invited BlackBoxVoting activists and researchers examine the certified Diebold voting equipment and demonstrate their insecurity for the Hacking Democracy documentary,94 afterwards vowing not to use their equipment again,95 and, after a predictable litany of lies and threats from Diebold,96 thus was quickly rendered a persona non grata by, in the collective, both the tripartite slate of corporate vendors authorized to sell in Florida, and public officials snaking all the way up the governmental pyramid up to the Secretary of State and the Governor of Florida themselves for the fallout of those company’s actions.97

After initially agreeing to enter a contract with the county after the county council voted to disavow Diebold’s equipment, ES&S ultimately spurned their attempted acquisition on the basis that they could not fulfill equipment deadlines and had to restrict themselves to serving long-time customers.98 The fictitiousness of this excuse is demonstrated by ES&S agreeing to deploy AutoMARK touchscreen electronic ballot marking devices that create a paper trail elsewhere, after the Leon County request, once the council of Volusia County voted 4-3 to abandon its Diebold equipment.99 Similarly, an attempt to reach out to the remaining state-qualified vendor, Sequoia, ended in failure when an arrangement established between the county and a local representative was overruled by the corporation’s CEO, who asserted that the company would not be accepting any more contracts for 2006 due to being at maximum capacity.100101

For their flaws, voting systems and modifications are tested and certified by federally-accredited testing labs and state commissioned testing authorities in order to ensure their compliance with certain standards designed to preclude the worst of the above — theoretically, anyways, but sometimes election vendors simply flaunt the law outright.

On November 10th, 2003 an audit conducted by the California Voting Systems and Procedures Panel of Diebold voting systems used in seventeen counties discovered that, in all seventeen counties, Diebold had engaged in unauthorized installations of software patches that were not certified by the state, and in three of its client counties the patches weren’t federally-certified, either. These patches were in use for at least three years. They failed to notify the Secretary of State of California of its proposed system modifications and admitted that it’s deployment of software without obtaining certification ran contrary to state and federal law.102103 SoS Kevin Shelley decertified and banned the use of the Diebold AccuVote TSx touchscreen voting systems104 (though his successor recertified them), and called upon the State Attorney General, Bill Lockyer, to pursue criminal charges for fraud against the vendor; however, he declined, and instead sought to pursue a monetary false claims judgement, which he, alongside BlackBoxVoting activists, won.105 But the fine was insignificant next to the profits Diebold made from selling the uncertified systems to counties, meaning no true consequences for breaking the law were resultant of the suit.

Indeed, in January of 2002 Diebold's Principal Engineer Ken Clark penned in a memo that “Strictly adhering to our release policies, the California change should also require a major version number bump to GEMS (because of the protocol change). We can't reasonably expect all of California to upgrade to 1.18 this late in the game though, so we'll slip the change into GEMS 1.17.21 and declare this a bug rather than a new feature. What good are rules unless you can bend them now and again.”.106

The story repeated itself again in late 2007 when the state of California attempted to subpoena ES&S voting system source code as a part of the state sanctioned UC Berkeley Top-to-Bottom review of electronic voting system security. ES&S initially ignored SoS Bowen’s demands for them to cede the source code for their InkaVote Plus voting system used in Los Angeles County,107 at the time, only — curiously — surrendering when she motioned for Iron Mountain, the company holding the originally certified source code in escrow, to release it to the state; indeed, ES&S lobbied for the state to only inspect the code that they gave them, not the certified code held in escrow, and for Bowen to withdraw her request to review it.108 It was, given the company’s dilatorialness, far too late for the source code to be subject to the Top-to-Bottom review, however, as it happened, it was immediately obvious that, just as with the Diebold AccuVote TSx source code, the version number for the deployed InkaVote Plus machines did not match that of the source code held in escrow, either suggesting a typographical error or an unauthorized modification to the voting system firmware.109 Given its unwillingness to let the state examine the escrowed source code, it’s most likely the latter, and use of the InkaVote Plus in Los Angeles County was suspended shortly thereafter.110

Additionally, about a month later the state discovered that ES&S had violated California Elections Code § 19213 by illegally deploying for use in polling places across multiple counties 1,000 units, costing taxpayers $5 million, of an uncertified and unauthorized version of the AutoMARK ballot marking device model that have been modified from a version previously approved for use by the SoS, without alerting the SoS and confirming that the modifications do not materially impair the performance or accuracy of the system. The systems weren’t even certified federally.111112

Even minor voting companies are in on the art of steal. MicroVote General Corporation113 was ordered to pay nearly $400,000 to the state of Indiana in civil penalties after they came under investigation negotiating hundreds of thousands of dollars in sales contracts with ten Indiana counties to deliver and service completely uncertified voting systems.114

As a semi-related addendum, as I'm not quite sure that this is expressedly illegal (though it certainly is extremely unethical), but there was a design flaw involving incompatible tolerances for the motherboards115 of 4,700 Diebold touchscreen voting systems across four counties in Maryland (Allegany, Dorchester, Montgomery, and Prince George) that led to unresponsive screen failures during voting in 2004, resulting in the manufacturer quietly recalling the boards and replacing them over the months. Oh, and they did not properly inform the Maryland State Board of Elections about this; indeed, they deceived them in a July 12th, 2005 interview, claiming that the upgrades would bring the devices up to date with the specifications of newer units, whilst omitting mention of the motherboard changes. They only thought to exhibit candor with Diebold apologist Linda Lamone, the director of the board.116

The saga of uncertified equipment or software patches does not, however, stop there. The federal Election Assistance Commission is theoretically charged with the regulatory authority and prerogative to revoke certifications from and otherwise punish voting machines manufacturers for running afoul the law, but history has shown the agency to be both feckless, impotent and captured by those very vendor corporations to effectively regulate them.

There is a certain amount of trust, or, more sneeringly, faith, involved in the business of electronic voting that is due between officials and voters, and the companies responsible, in part or in whole, for administering statewide elections. We have seen that trust broken and betrayed on many occasions, but perhaps, that is simply inherent to the companies themselves and the private equity that controls them, and the nature of those they employ to deliver on their promises.

The roster of employees at Global Election Systems117 included ex-felon Jeffrey W. Dean, a former tech consultant for the large Seattle law firm Culp, Guterson and & Grader, who was convicted in the 90s for the highly sophisticated computer-aided embezzlement of $465,341 from said firm and the digitized alteration of financial records, who served as the senior vice president of Global after 2000 and then made head of research and development with full, unfettered access to all components of their voting system, which was used in Washington, Florida and elsewhere.118119 Diebold denied enlisting him after its acquisition of Global, but depositional records demonstrate that he returned as a consultant in mid 2002.120

Meanwhile, convicted cocaine trafficker John L. Elder worked for Global's and Diebold's ballot printing and absentee ballots handling divisions.121

Then there are the companies that program the voting machines when the vendors themselves aren't charged with such activities. These election subcontractors handle programming, servicing voting equipment, results reporting, and even acceptance testing for the jurisdictions, and constitute a clique of shadier, less known, even more centralized and sometimes equally unreliable and/or partisan outfits such as Triad Governmental Systems Incorporated,122 responsible for election support before, during and after voting in seventy-three Ohio counties, Command Central,123 based in an indistinct storefront in St. Cloud, Minnesota and which performs programming for 2,000 jurisdictions across thirty-four states,124 LHS Associates125 of New England, and, formerly, the non-corporate Center for Election Systems at Kennesaw State University (KSU-CES) of Georgia.126 Harp Enterprises Incorporated of Kentucky,127 Scytl, SMARTech, among many others that I do not know and cannot name handle election reporting.128 Even if these outfits are not explicitly beholden to private interests, it would be easy to implant malware on the voting systems they service by burglarizing and/or hacking their company computers first, which they use to prepare programming packets.

To be specific, LHS Associates, which is entirely responsible, to my knowledge, of the programming of voting machines on the county- and township-level, from legacy Diebold optical scanners to modern Dominion optical scanners, in the states of New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Vermont, Maine, and Rhode Island, amongst whose key executives some are ex-convicted felons implicated in the drug trade.129 Fittingly, the company would, back around 06, troubleshoot the number of memory card failures on the serviced states’ optical scanners (which were and are quite common130) by doing something very illegal, at least in Connecticut: swap out memory cards, containing instructions that direct the machines’ reading of vote data and can be used to introduce viral malware, during voting, during elections, in order to deal with procedural difficulties. Said memory cards would be stored soundly in the trunk of a car, idling outside without supervision until they received a call for assistance. Chain of custody is, after all, a famous substitute for toilet paper.131

"I mean, I don't pay attention to every little law. It's just, it's up to the Registrars. All we are is a support organization on Election Day" — the Director of Sales and Marketing for LHS Associates, 2006.132

Vendors are proven to be untrustworthy, uncompromising, negligent and even criminal.133134 But to complete their regulatory capture they take advantage of election authorities’ willingness to be swayed through their bank accounts, and facilitate the corporate infiltration of rule making bodies to bend their decisions in their favor.135

A long-time administrator of the Maryland State Board of Elections, Linda Lamone, was a wholehearted Diebold apologist who sang praise to the perfectability of the company's products and did everything in her power to reinforce the company's tireless pitch that all the calamitous excesses of electronic voting were instead brought about by human errors relating to the operation of the equipment.136137 She even explicitly endorsed the Diebold, and allowed them to utilize her likeliness to market their ExpressPoll e-poll book138 which caused disastrous voting meltdowns during the 2006 primary elections, under her watch.139140 In 2003, despite multiple studies confirming grave vulnerabilities in the Diebold AccuVote TS, one of which was commissioned by the state, the Board of Elections nevertheless moved forward with its $55.6 million contract with Diebold to supply those touchscreen voting machines to all jurisdictions across the state.141

In August of 2007, in response to the corporate voting system certification avoidance scandal referenced above Debra Bowen issued a wave of election system decertifications (including Diebold stock and the ES&S InkaVote Plus) and then conditionally recertified them (excluding the InkaVote Plus) under the stipulation that counties can only purchase those touchscreen devices for disabled voters. The entire stock of paper audit trails produced by the touchscreen voting machines would be manually recounted to ensure, with reasonable certainty, the correctness of the count. This recount would not be paid for by the counties or the candidates, but rather by the companies selling the ADA-compliant voting machines.142 Expectedly, this rule was unpopular with the vendor corporations and the various peons on their bankroll, including Los Angeles County Registrar of Voters Conny McCormack, an avid e-voting defender who, like Lamone, had been recruited for a marketing position with Diebold,143 and lead the charge against the SoS's new rule. She was deeply concerned... about how Diebold's bottom line would be negatively impacted by the rule.144

McCormack said Bowen’s order requires the county's vendors to pay the costs of that recount, which she estimated at $400,000 per election.

“I think we have to see what the vendors are going to say about that”, McCormack said. “The vendors aren't going to make much money in Los Angeles County if they have to pay $400,000 for the recount.”

But Supervisor Gloria Molina upbraided McCormack for her concerns about the vendors’ profit margins.

“I think you are walking close to the edge”, Molina said. “I don't understand why you are so protective of the vendors. You keep saying you are concerned about what this is going to cost them.

“It’s really none of our business. It shouldn't be in our interest to protect the vendors’ profits.”

Top Utah election officials were enamored with Diebold back in the 2000s. Lieutenant Governor Gary Herbert, unabashed Diebold defender and, of course, is one of those people that accuses anyone who is skeptical of counting votes on an easily hackable computer of being a luddite and a conspiracy theorist. The conflicts of interest came to a head after March 2006, when twenty-three-year Emery County Elections Director Bruce Funk invited computer scientists from BlackBoxVoting, including Harri Hursti, to examine the security of the Diebold AccuVote OS optical scan voting system in order to demonstrate his voting concerns practically. Superior Utah election officials, and other county commissioners, did not thank him for exposing systemic defects that could collapse elections in Emery County, and open up elections across the state and the country to compromise. They did not demand Diebold fix their products or to instead refund their contract money, nor did they sue them. Instead, they lambasted him for turning in the electronic voting devices for inspection, locked him out of his office and quickly relieved him of his duty.145146

Phillip Foster, a Sequoia salesman indicted in 2001 by a grand jury for crimes relating to a Louisiana kickback bribery scandal involving an election administrator responsible for servicing election equipment and oversaw the purchase of unnecessary Sequoia equipment, was granted prosecutorial immunity for his testimony in the scandal and was not tried. Foster thereafter rose in the company and eventually came to serve as the Vice President Administration & Strategies.147 He served on the Palm Beach County Election Technology Advisory Committee, from September 2005 through May 2006 and continues to advise the county’s elections supervisor.148

Former California Secretary of State Bill Jones, who helped develop an election “modernization” plan that involved decertifying and phasing out the state's antiquated mechanical voting equipment with high-tech optical scanners and touchscreen voting machines in all fifty-four counties without electronic voting equipment, and sponsored Proposition 41 which allocated $200 million to counties to acquire privatized voting systems and was financed and lobbied for by ES&S and Sequoia, ultimately leaving the office in 2003 to become a top consultant for Sequoia. The officials working under his administration's employ had similar conflicts of interest: his former top aide departed to work as a vice president for business development at the same company, while Alfie Charles, Jones’s press secretary during his tenure, simultaneously sat on the panel that recommended to Jones which machines could be sold in California, and worked on communications for Proposition 41. He went on to work for Sequoia as a spokesman in 2002 soon after the passage of P41.149

After serving as the chief of elections under long-time California Secretary of State March Fong Eu, potent e-voting counter-critic Deborah Seiler departed for a job with Sequoia in 1991 after working in the state legislature for a year, before transferring to Diebold as a sales representative,150 who she helped deliver nearly 1,200 non-federally or state certified touchscreen voting machines to Solano County, among other activities, legal or otherwise. She was also the chairwoman of the California Association of Clerks and Election Officials at the same time. But her saga through and about the revolving door didn’t stop there; eventually she returned back to elections, and was hired as assistant registrar at Solano County in 2004151 before becoming Registrar of Voters at San Diego County in 2007.152

Former Riverside County Registrar of Voters Mischelle Townsend was alleged to have failed to file conflict-of-interest forms from 1998 to 2002 and failed to disclose the source of her husband’s income, and illegally accepted travel and lodging fares from Sequoia Voting Systems in order to facilitate her appearance in an infomercial marketing their products.153154 She was also, as the supposed poster-child of electronic voting, responsible for making Riverside County one of the first counties in the state to use touchscreen voting machines for all registered voters in 1999-2000, which were manufactured exclusively by Sequoia.

Edwin B. Smith III, then serving as the vice president for compliance and certification at Dominion Voting, and who formerly served as vice president of manufacturing, compliance, quality and certification at Sequoia Voting Systems, and, before that, the operations manager at Hart InterCivic, was appointed to the Board of Advisors of the Election Assistance Commission in 2009, which is charged with oversight functions of the very companies Smith served in.155 The same Edwin Smith who, as stated above, spent years soliciting the advice of questionable crackpot contractors over Princeton computer scientists who he threatened with legal action over infringing upon "proprietary corporate trade secrets" if they conducted the independent inspection of the source code of their touchscreen voting system as commissioned by New Jersey.

In 2004, Common Cause reported that Diebold Election Systems had wooed Jack Abramoff's firm Greenberg Traurig with a donation of $275 million. Abramoff and Greenberg Traurig represented OH-18 House Representative Robert W. Ney, who introduced and sponsored the Help America Vote Act in the House in 2001 until its passage, which disbursed $3.9 billion in taxpayer-funded kickbacks to electronic voting vendors like Diebold.156 A payment stub and pre-check-register revealing a $12,500 payment for the month, made from Diebold to Greenberg Traurig, was discovered in a dumpster at Diebold’s McKinney, TX facility in July of 2004 by electronic voting watchdog group BlackBoxVoting.157158

An issue incumbent to the genesis of the computerized voting era was that of equipping DREs with paper audit trails that could be recounted in the event of an error or fraud, but this requirement, though seemingly common sense, was opposed fiercely by disability rights groups implying that only unverifiable machines serve the needs of disabled voters, leading to some to suggest that they were on the bankroll of cynical vendor corporations who benefitted from cheap to manufacturer, expensive for counties to purchase paperless voting machines.159

The National Federation of the Blind, for instance, had, in 2004, championed these controversial, paperless voting machines. It attested not only to the machines' accessibility, but also to their security and accuracy; neither of which is within the federation’s areas of expertise, and was contradicted by a wellspring of scientific research already available to the public at the time. Troublingly, these assertions were not made from a stance of neutrality, as Diebold had allocated a gift of $1 million, which they accepted, to cover the expenses of a new training institute.160

The American Association of People with Disabilities, according to member Jim Dickson, who paper trail-opponent and HAVA signatory Senator Christopher Dodd appointed to the EAC’s Board of Advisors, had received $26,000 from voting machine companies in 2004.161

The long saga of influence-peddling by election vendors in Georgia began in 2002 despite the legislature-backed introduction of a statutory requirement necessitating that voting systems leave behind an independent audit trail of each vote cast.162 Subsequently, Secretary of State Cathy Cox, another such Diebold apologist who repeatedly allowed the company to utilize her likeliness to advertise their products,163 negotiated a deal with the company to purchase unauditable, and therefore illegal, paperless DREs.

This bargain, evidently, necessitated the $54 million164 (plus another $15-or-so million for warranty extensions beyond 2002) makeover of Georgia’s voting systems with unverifiable touchscreen DREs, and that, in order to facilitate the transition in the five months Diebold had to prepare the state for the November 2002 election, the state should engage the complete abdication of its election administrative duties and effectively surrender its sovereignty to corporate contractors working for Diebold, who should service and support the state’s centralized and standardized voting system and county election offices, train poll workers, open and close polling stations, design ballots — a completely privatized and corporatized system.165166 This arrangement still holds to this day, just with ES&S in 2018, and finally Dominion, instead, just even more centralized with KSU-CES out of the picture. At the very same time, the lobbyist for Diebold, the preceding Georgia Secretary of State Lewis Massey, and Cox’s former boss, then joined the lobbying firm of Bruce Bowers.167

The Director of Election Administration under Cox, Kathy Rogers, who was cited as casting a considerable influence over Cox’s final decision,168 is an ardent defender of the faith when it comes to unverifiable, faith-based electronic voting, rejecting the near-consensus on the hackability of voting machines, especially Diebold ones. In 2006, a bill requiring a verifiable paper record of each ballot, introduced in the Georgia legislature at the urging of election-integrity advocates, failed after Rogers opposed it.169 It thus came as no surprise that she should accept a job at Diebold at the company’s enjoyment in December of that year.170 In the present she serves as the senior vice president of ES&S, and promoted its sanctity (and its unverifiable touchscreen electronic ballot marking devices) through hell or high water.171

Karen Handel, whose successful 2006 Secretary of State campaign integrated ideas of election integrity and vote-count verifiability,172 seemingly turn-tailed her position upon inauguration, defending173 and defeating174 a grassroots election integrity suit175 to decertify Georgia’s unconstitutional voting system in the three years it wended through the courts, all the way up to the state Supreme Court. Shortly after winning election in 2006 Handel appointed Rob Simms as Deputy Secretary of State, who worked as a partner to Lewis Massey’s Atlanta-based Massey & Bowers lobbying firm.176 She received $25,000 in campaign contributions from employees and family members associated with the lobbying firm.177

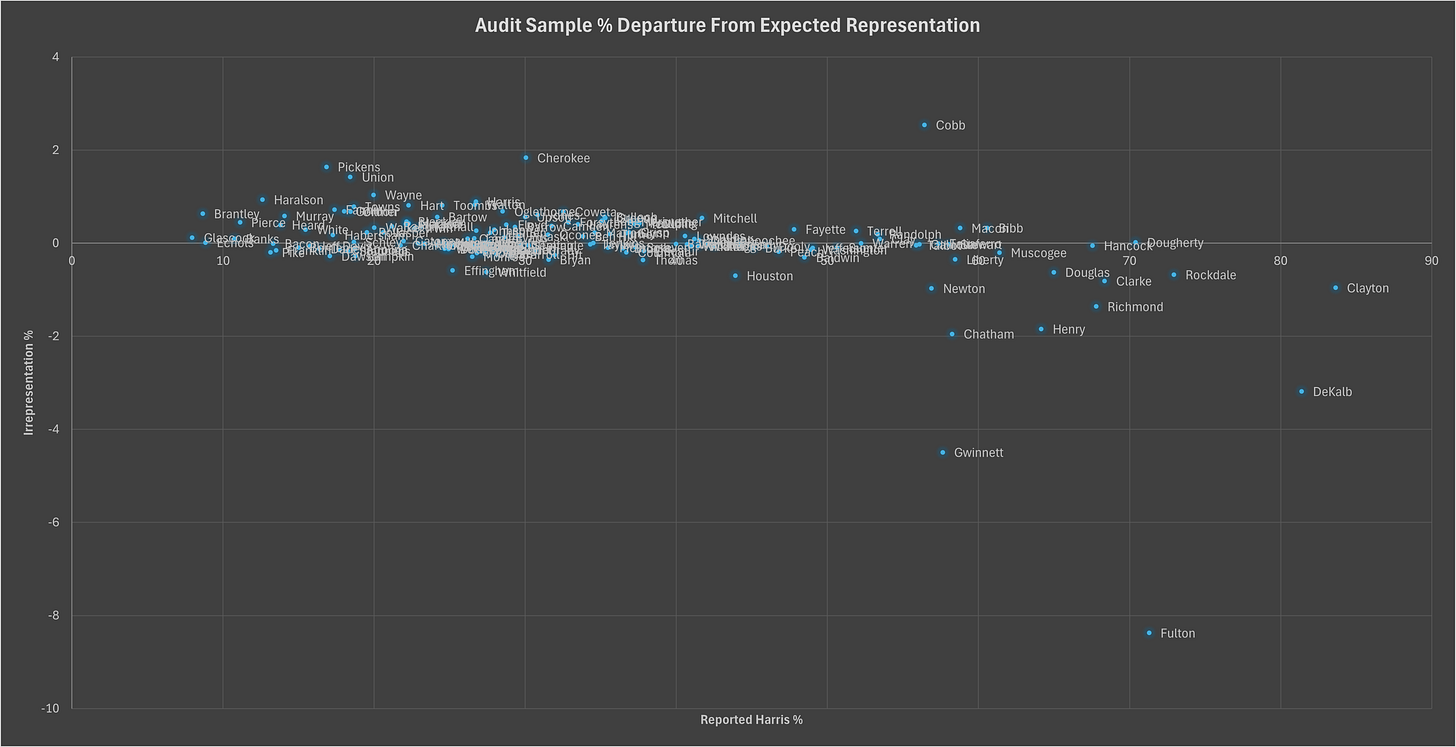

Later litigation by the plaintiffs of the Donna Curling et al. v. Brad Raffensperger et al. in mid-2019 was more successful, and achieved the suits goals of decertifying the unverifiable AccuVote-TSx DREs and forcing a court-ordered transition to paper balloting.178 Rather than move to cheaper and more reliable hand-marked paper ballots processed by optical scanners, against all expert counsel,179 state administrators sided with proposals to replace the aging DREs with almost as unverifiable, for reasons discussed later, electronic ballot marking devices and machine-marked paper ballots180 — a 2018 measure to implement universal machine ballot marking was defeated by election integrity advocates despite vigorous corporate lobbying181 but was rammed through in 2019 by the state legislature anyways.182 The first of these proposals, endorsed by Governor-elect Brian Kemp earlier in the year and before the landmark ruling, was to back a >$100 million ES&S bid to purchase ExpressVote machines.

In 2019 Kemp established the Secure, Accessible and Fair Elections Commission to initiate an appraisal process of multiple contracts from six different prospective vendors, acquired through a request for proposals submission.183 Worries that the bid selection process was pre-determined to favor ES&S proliferated after Kemp’s cabinet appointments came to light.184 David Dove, Kemp’s appointed executive counsel, worked on an advisory board for ES&S, and attended a Las Vegas conference hosted by them in 2017.185 His deputy chief-of-staff, former state representative Charles Harper,186 was a lobbyist for the office of Secretary of State during Kemp's former incumbency from 2012 through 2017, before pre-registering as a lobbyist for ES&S. Additionally, John Bozeman, formerly the head of legislative affairs for Georgia’s former governor, Sonny Perdue, registered to lobby for ES&S.187

It then came as a surprise when the state instead signed a $90 (later $130) million contract with Dominion instead.188189